Throughout the centuries, women have been involved in making art, whether as creators and innovators of new forms of artistic expression, patrons, collectors, sources of inspiration, or significant contributors as art historians and critics.

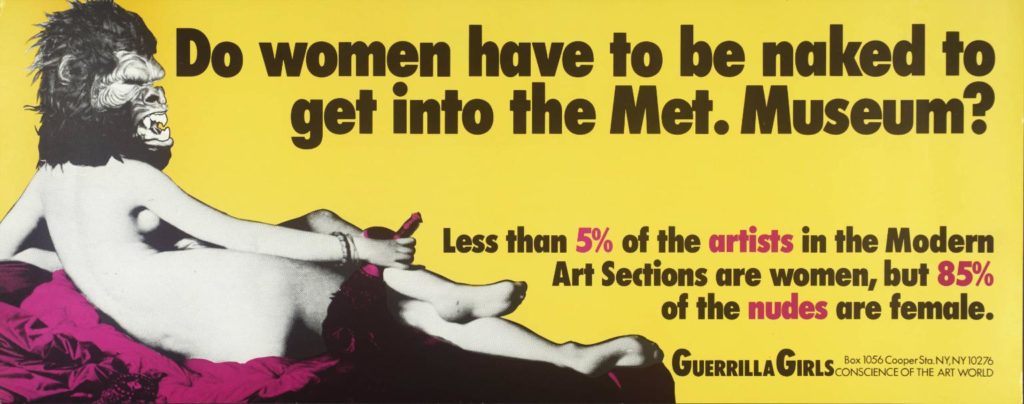

Women have been and continue to be integral to the institution of art, but despite being engaged with the art world in every way, many women artists have found opposition in the traditional narrative of art history. They have faced challenges due to gender biases, from finding difficulty in training to selling their work and gaining recognition.

British artist Mary Beale was a successful portraitist in the late 1600s, but much of her success was attributed to the fact that her husband oversaw their studio and presented her works as experiments in the painting methods he developed. Gwen John, whose self portrait appears isolated and scrutinising, struggled for recognition in a field dominated by men, including her accomplished brother Augustus.

Despite being marginalised and sidelined by the male members of the group, artists like Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr pushed to be card-carrying members of the Vorticist movement. French painter Francoise Gilot forged a visual style and identity entirely her own despite being known mainly as Pablo Picasso’s lover and working in close proximity to major artists like Henri Matisse and Fernand Léger in the 1940s. Surrealist women painters and sculptors like Eileen Agar and Louise Bourgeois were iconoclasts in their explorations of mind and body, developing fluid, intimate, and openly sexual subject matter. With a renewed sense of agency and confidence through their art, what issues have women artists chosen to address? Because of the different societal and developmental contexts since the 1960s, building upon those from the early 20th century, many women artists currently address personal and transnational issues of identity, exploring global and diasporic politics. The works of exile artists such as Mona Hatoum and Shirin Neshat tell stories of loss and insight through conflicting countries, cultures, and gender roles. Meanwhile artist Sonia Boyce’s film, photographs, and paintings bring racist stereotypes to light.